IDEALS – Authenticity

What Is Authenticity?

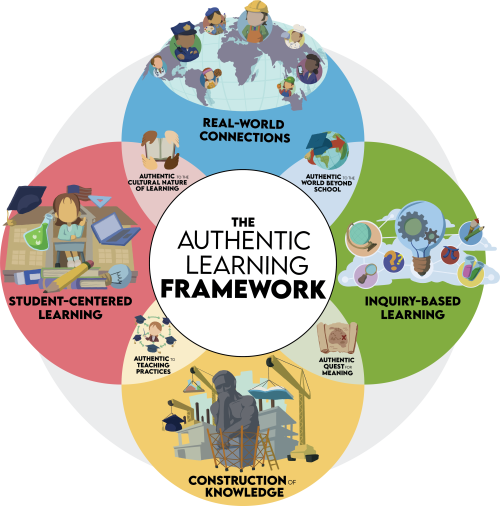

The Authentic Learning Framework supports teachers in the development of student-centered learning experiences. The framework is grounded in a scaffolded model where learners build on their identities, cultural backgrounds, and existing knowledge through inquiry and discourse to deepen their understanding and enrich their sense of purpose in the world around them.

The Authentic Learning Framework

As we explore the idea of authentic learning practices, the research offers a view of authenticity not as a single idea but instead as a collection of components. These components provide students with varied opportunities to connect with the content in personally meaningful and relevant ways to ensure retention and application of knowledge across contexts. Research has shown that teachers can emphasize learning as meaningful when it is student-centered, collaborative, contextual, and integrated with community and society (Anderson, 1983; Atkinson & Schiffrin, 1977; Ausubel, 2000; Bransford et al., 2000; Dewey, 1966; Piaget, 1972). These types of learning experiences increase positive emotions around learning, garner higher perceptions of relevance and long-term understanding, and activate student engagement in learning as well as an intrinsic motivation to learn (Nachtigall et al., 2022; Parsons et al., 2021; Jeter et al., 2019; Kuhlthau et al., 2015). Authentic practices not only help teachers to more fully engage students, but also allow students to gravitate toward learning that resonates with them.

Authentic Learning Practices Center on the Following Components:

We often use the term “student-centered learning” to describe a shift in teaching focus from the teacher to the student. This idea can include aspects of student agency (Manyukhina & Wyse, 2019; Moses et al., 2020; Reeve & Shin, 2020), scaffolded learning environments (De Backer et al., 2016; Mariage et al., 2019; Schwartz et al., 2021), and the cultural nature of learning (Esteban-Guitart & Moll, 2014; Hammond, 2015; Kelly et al., 2021; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2018). Student-centered learning emphasizes the student’s role in constructing their own knowledge. These types of guided learning opportunities help students make purposeful learning decisions that connect to their existing cultures, experiences, and understandings (Colter & Ulatowsky, 2017). A student-centered learning environment allows teachers to serve as facilitators throughout the process, supporting students as they become independent learners (Lee & Hannafin, 2016; Reeve & Shin, 2020).

Construction of knowledge forms the foundation of constructivist theory, building on the idea that there is no knowledge independent of the meaning that we construct as learners (Fox, 2001; Piaget, 1972; Vygotsky, 1978). How we construct knowledge is grounded in the work of Piaget, but these ideas have also expanded through recent studies in cognitive psychology, brain research, and human development, which have shown how complex interactions between learners and their environments result in structural changes to the brain’s neural networks (Liu et al., 2017; NASEM, 2018). These neural networks make up the long-term memory of individuals and are continuously extended and reshaped as new information is received from the environment (Liu et al., 2017). Our prior experiences are shaped by educational, social, and cultural experiences both in and out of the classroom (Liu et al., 2017; NASEM, 2018).

Inquiry-based learning is an active process that begins with and is guided by relevant questions (Chatterjee et al., 2009; Kuhlthau et al., 2015). Teachers can facilitate the inquiry process by helping students to ask good questions, find relevant information, and think through their conclusions, inferences, and solutions (Kranzfelder et al., 2019; Ligozat et al., 2017). As students work to answer questions through research, analysis, and collaborative discourse, they synthesize and make sense of information and ideas that enable them to deepen their knowledge and share their new understanding with others. Through a focus on inquiry, we allow a student’s own curiosity to drive how they construct their knowledge.

Connecting learning to the real world helps students see how their learning might be applicable in the future, while also motivating them to attempt to apply their learning in meaningful ways (Darling-Hammond et al., 2021). These real-world connections can help students develop aspirations about what they want to do after school, since they are positioned to imagine themselves trying different future paths as they learn (Singer et al., 2020; Beier et al., 2018; Koomen et al., 2018). When teachers deliberately integrate the school setting with the real world, students can more easily transfer skills upon entering the workforce (Osher et al., 2020).

How Does Authenticity Relate to My Work?

The Importance of Authenticity in Schools

Authentic learning aims to support educators in developing student-centered learning experiences grounded in a scaffolded process where students build on their identities, cultural backgrounds, and existing knowledge through inquiry and discourse to deepen their understanding and enrich their sense of purpose in the world around them. Educators are authentic in their practice by being true to the content, the learning process, and the science that supports how people learn. Students develop a connectedness to their learning through their personal histories, aspirations, or cultures. Authentic learning has at its heart the aim to infuse learning with purpose and meaning so that students develop the skills necessary to fully engage in life and the world.

Learn More About Our Research

Resources & Job Aids for Schools

- Collection of Professional Learning in Authentic Instruction

- Authenticity Infographic

- Authentic Learning and Teaching Chart

- Authentic Lesson Reflection Tool

- Productive Discourse Chart

- Integrating Technology

- Components of Authenticity – Authentic Use of Technology

Looking for FREE lesson plans?

Check out our Lesson and Engaging Activity Repository & Network (K20 LEARN) for authentic lesson plans, instructional strategies, technology tools and more.